Web Crawling Part 1 - Scraping with Scrapy!

So we know the internet is a goldmine for useless information - a mishmash of human knowledge. Information that speaks so loudly that sometimes it’s hard to hear what really matters. How can we filter out the noise, and get at the important stuff?

Web scraping allows us to access the gems of data embedded within a web page. And much like Perl was the original Swiss Army Knife for the web, it seems Python has stepped in and become the modern programmer’s Macguyver Kit, seemingly having a tool/framework/library that fits almost every situation. And web crawling/scraping is no different. Introduce, Scrapy, an amazing library for quickly developing, testing, and deploying your web scrapers.

So what is Scrapy again? Scrapy is both a web crawler and web scraper. What does that mean? First, that means that Scrapy has the ability to navigate a sites structure by following links to different pages within or oustide of the site’s domain. Second, as Scrapy navigates these webpages, it can then peel away the layers of structural information on a webpage (i.e. HTML) to access only the specific content that you want. This makes it very useful for extracting globs of raw data from the web.

What we will be scraping: 2014 NFL Season Play-By-Play Data

What you need to proceed:

- Python 2.7

- Scrapy

- IPython

- Anaconda (All-in-one install)*

*May require running conda install scrapy from the command line if not available after install

Overview:

- First Steps

- Scrape Before You Crawl

- Let Your Spider Do The Crawling

- Scalpels and Sledgehammers

- A Crawling Spree

- Legalese and Scraping Etiquette

- Wrap-Up

Here, in Part 1 we’ll focus on leveraging the Scrapy framework to quickly parse all of the play-by-play data for the 2014 NFL season. In Part 2 we’ll build off our knowledge here to implement a full-fledged web crawler to parse multiple seasons of NFL game data.

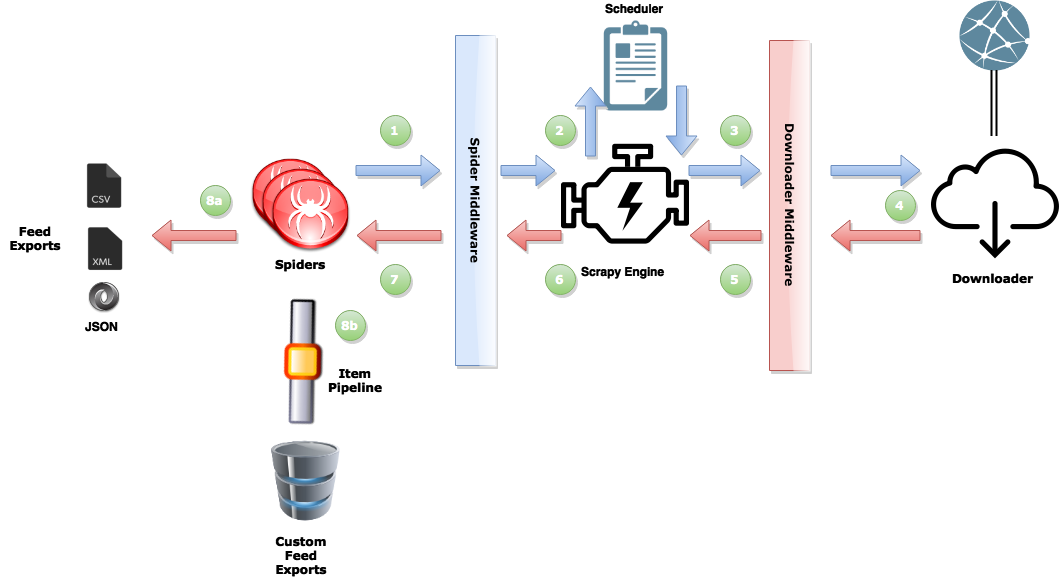

A dataflow overview

In this walk-through we’ll focus mostly on developing a basic spider, and then we’ll hit the rest of the framework in Part 2. But, if you’re really curious, and can’t stand the suspense, you can take a look here for a more detailed description. But for the purpose of this introduction the general process goes like this: The spider schedules requests for download (1), the engine manages these requests and then executes them concurrently (2,3). When the response is available (4), the engine sends it back to the spider (5,6), who scrapes the response (7) and either returns more requests to the scheduler (1), or returns scraped items from the webpage (8a,8b).

First Steps…

To begin implementing the spider we need to setup our environment so that Scrapy can know where to find the items necessary to execute your spider. To do this we use the command scrapy startproject nfl_pbp_data to automatically setup the directories and files necessary for our spider. So find a directory you would like the project to reside, and execute the above from your command line. You can skip the next section if you’re already familiar with XPath and web scraping.

Recon

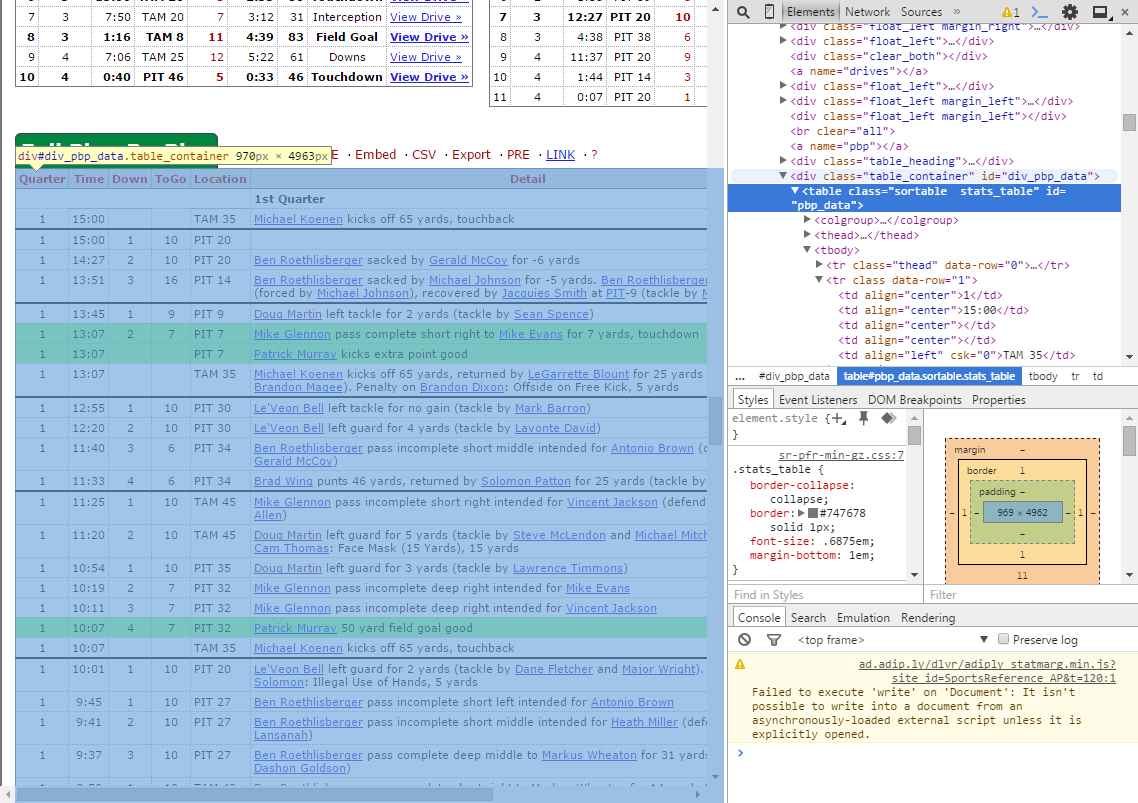

But wait… Before we continue we need to get an idea of where our data is located within the webpage. This requires a bit of recon on the page to determine it’s layout, and how best to access the information. The best tools to use for this nowadays come with every major browser (Firefox, Chrome, Safari, IE, Opera). They are normally hidden away in some developer tab/option that may not be readily apparent until you search for it. If in doubt, check here.

Now, for this walk-through we’re going to scrape the 2014 NFL season play-by-play data. This will be a good example to get a basic understanding of the scraping process, and might even prove useful to anyone who likes playing with the numbers. This data is available for free use and can be obtained from a number of sources. We’ll grab our data from pro-football-reference.com, which for the past few years has been given access to the official play-by-play data feeds pushed directly through NFL.com.

So now fire up your favorite browser and developer tool, and head on over to . The first thing to notice here is that the data is setup in a very nice, tabular format. It’s also not polluted with ads or other extraneous information. this will make our job a whole lot easier.

To access the particular information we want the Scrapy framework allows you to query the page using XPath or CSS selectors. Here we’ll be using XPath selectors, but you can easily substitute our queries for the CSS selector equivalent. I won’t be going into much detail about XPath, but I will try to explain the XPath queries we choose and why we’ve chosen them. For an excellent overview and reference for XPath, you can take a look at w3schools and MSDN.

Since we’ll be extracting the game data, we actually need to click one of the boxscore links. This will take you to a game summary page that has a wealth of information, including the exact information we’re looking for - the play-by-play data. If you inspect the tag containing the play-by-play data you’ll see that it resides under <table id="nfl_pbp_data".... And this is where we’ll begin constructing our XPaths.

Scrape Before You Crawl - Scrapy Shell

So one of the most useful tools in the Scrapy toolbox is the Scrapy Shell. It allows us to pull a web response into the iPython shell environment, which acts like a sort of playground for us to toss around the html until we’ve figured out how to extract our data.

What’s IPython?

Python actually comes with it’s own shell, but IPython adds a bevy of features that essentially turn the shell into a programmer’s playground. If you find it really useful, you may want to also keep a watch out for Jupyter, the platform-agnostic versions of IPython that will be compatible with many other languages (C#, C++, Javascript, Perl, Haskel, R, Ruby, etc…).

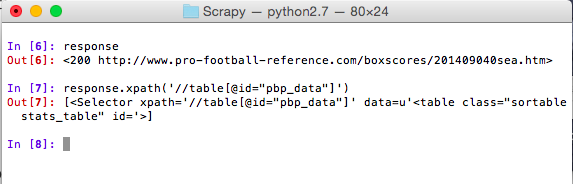

You can fire up the Scrapy shell by traveling to the top-level directory of your project and running scrapy shell "http://www.pro-football-reference.com/boxscores/201409040sea.htm", which should bring up an IPython terminal. If not, refer to the IPython installation link above for some troubleshooting guidance.

The data that we want to access is located under <table id="pbp_data"> so we’ll start by using that as the start of our XPath.

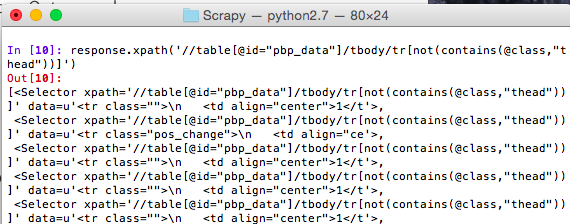

In the first line you can see that the object response holds the response information captured by the Scrapy shell from our web address. And then in the second line we can see that the XPath returns an object with the results of our query. These objects are called selectors and are one of the primary weapons for carving out your data. From this selector we can now build out a more complex XPath that finds all table rows of the game data and then filters out any header rows (which conveniently are labeled under the class thead).

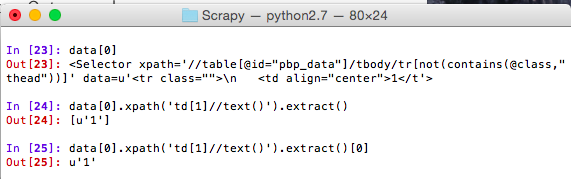

When you run this you may notice that Scrapy returns a list of objects from its query. This is because the XPath we’ve used extracts each table row and then returns the results as a list. So we can access each item just like a normal python list.

So you might be wondering, okay so I’ve queried my data, but how do I actually extract the raw data? That’s simple you use the method extract. Now, before you get carried away attaching extract to the end of all of your selector queries, realize that extract always returns a list, whether it grabs one item or a hundred. So if you plan on actually storing this data you will need to pull it out of the list object.

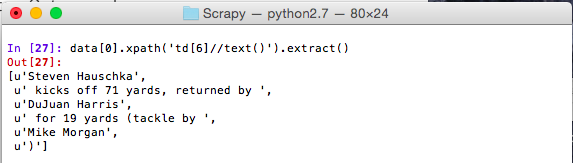

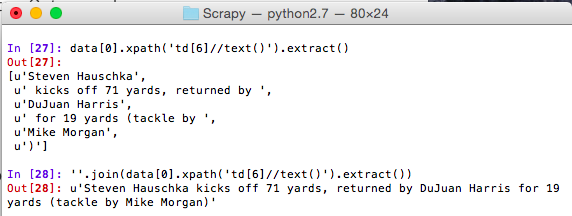

It becomes slightly more complex if extract returns multiple items in the list. Consider this:

XPath Note:

The queries above use the // to indicate a recursive descent through the html hierarchy. This allows the query to search the entirety of the HTML document, or in the case of extracting a specific column, we can search through the entire <td> tag.

Here the data extracted is not a contiguous text node so our selector works until it finds all of the text nodes and then returns them in a list. We can extract the data from here using python’s nifty join method. Note: This works well in our example, but may not be the best representation of other data sets. Figure out what works best for you.

Let Your Spider Do The Crawling

By now, hopefully you feel comfortable scraping web data using selectors and the Scrapy shell. From here we’ll turn our attention back to implementing a functional web crawler using the rest of the Scrapy framework. First, go to your spiders directory (from the top level project directory it will be under nfl_pbp_data/spiders) and create a new python file called NFLStatsSpider.py. This will hold the guts of our spider, and is where all of the spiders you want Scrapy to use should reside. Now insert the code below as our basic template.

import scrapy

from scrapy.spiders import CrawlSpider, Rule

from scrapy.linkextractors import LinkExtractor

class GameDataSpider(CrawlSpider):

name = "nfl_pbp_data"

start_urls = ["http://www.pro-football-reference.com/years/2014/games.htm"]

def parse_game_data(self, response):

pass

Explanation:

CrawlSpider: one of the generic spider classes Scrapy provides that adds some additional functionality to make crawling and scraping even easier. Here, we use CrawlSpider as our base class.

name: the name of our spider. This is how Scrapy references our spider. You don’t have to tell it the filename, or update some huge configuration file, just set the name attribute, and anytime you need to reference your spider, you can call it by that name.

start_urls: the initial urls fed to our spider that begin the crawling process.

One of the benefits of using the CrawlSpider class is that it allows you to set rules for easily extracting links for your spider to scrape. The rules have several options, but the most important ones are the LinkExtractor object and the callback argument.

Here we use the LinkExtractor to specify which links we want to follow using a regular expression. Again, we can use the scrapy shell as a scratchpad to figure out what works. Then, we use the callback argument to specify what method to use for scraping each of the extracted links. And with that, we arrive at the final piece of today’s discussion. The scraper.

Scalpels and Sledgehammers

In Scrapy the parser’s job job is to extract data from a response and return either data items or more requests. In this example we’re using the LinkExtractor to parse the requests we need to follow so we only need to return data items. This is actually much easier than it sounds since we’ve already done the hard part of determining the correct XPaths to use to extract our information. The only addition at this point is to take the extracted data and compile it into an object to be returned to the spider. For this Scrapy uses Item objects whose function is almost identical to Python dictionaries. The item objects are essentially a dictionary wrapper that informs Scrapy that there are scraped items to process. Because it is a dictionary we can describe our data as we extract it.

def parse_game_data(self, response):

for row in response.xpath('//table[@id="pbp_data"]/tbody/tr[not(contains(@class,"thead"))]'):

play = {}

play['game_id'] = [game_id]

play['date'] = [date]

play['play_id'] = [play_id]

play['quarter'] = row.xpath('td[1]//text()').extract()

play['time'] = row.xpath('td[2]//text()').extract()

play['down'] = row.xpath('td[3]//text()').extract()

play['togo'] = row.xpath('td[4]//text()').extract()

play['location'] = row.xpath('td[5]//text()').extract()

play['detail'] = row.xpath('td[6]//text()').extract()

play['away_points'] = row.xpath('td[7]//text()').extract()

play['home_points'] = row.xpath('td[8]//text()').extract()

play_id += 1

# yield the item so that the scrapy engine can continue

# processing web requests concurrently

yield play

Here we are able to extract all of the game data and assign it to our Item object using whatever keys we choose, rather than having to define this information ahead of time. This is an added convenience in the newer versions of Scrapy that allows you to begin creating your scraper without predefining your data.

In the above code we also leverage the power of XPath by first querying for all rows of game data, and then again upon iteration we query each specific row to extract exactly the information we want. This is an approach I call Scalpels and Sledgehammers, and is one of the powerful features of the Scrapy selectors. We can use the general selectors to create queries that smash up the data into large chunks, and then fine-tune them to make precision cuts that extract the real gems.

A Crawling Spree

And finally we get to the fruition of our hard work, and that is executing the spider and letting it do it’s thing. The code below is the final version of the code for our spider.

import scrapy

from scrapy.spiders import CrawlSpider, Rule

from scrapy.linkextractors import LinkExtractor

class GameDataSpider(CrawlSpider):

name = "nfl_pbp_data"

start_urls = ["http://www.pro-football-reference.com/years/2014/games.htm"]

# the comma following the first item is REQUIRED for single rules

rules = (

Rule(LinkExtractor(allow=('boxscores/\w+\.htm')), callback='parse_game_data'),

)

def parse_game_data(self, response):

# uses the filename as the game id that takes the form yyyymmdd0hometeam

# (i.e. 201409040sea) - purely a convenience choice

game_id = response.url[response.url.rfind('/')+1:-4]

date = game_id[:4] + '-' + game_id[4:6] + '-' + game_id[6:8]

play_id = 1

for row in response.xpath('//table[@id="pbp_data"]/tbody/tr[not(contains(@class,"thead"))]'):

play = {}

play['game_id'] = [game_id]

play['date'] = [date]

play['play_id'] = [play_id]

play['quarter'] = row.xpath('td[1]//text()').extract()

play['time'] = row.xpath('td[2]//text()').extract()

play['down'] = row.xpath('td[3]//text()').extract()

play['togo'] = row.xpath('td[4]//text()').extract()

play['location'] = row.xpath('td[5]//text()').extract()

play['detail'] = row.xpath('td[6]//text()').extract()

play['away_points'] = row.xpath('td[7]//text()').extract()

play['home_points'] = row.xpath('td[8]//text()').extract()

play_id += 1

# sanitize extracted data

for key in play.keys():

# no empty keys

if not play[key]:

play[key] = ''

# join lists with multiple elements

elif len(play[key]) > 1:

play[key] = ''.join(play[key])

else:

play[key] = play[key][0]

# yield the item so that the scrapy engine can continue

# processing web requests concurrently

yield play

The spider can now be executed by moving to the top directory of your project and executing scrapy crawl nfl_pbp_data -s DOWNLOAD_DELAY=5 --output_file=game_data.csv.

Options meaning:

- DOWNLOAD_DELAY: Controls the time between requests. This is a VERY important part of crawling websites. Please be kind. See note below.

- output_file: The file to write the scraped data to. Scrapy supports the following popular formats: JSON, XML, and CSV. In Part 2, we’ll see how using an item pipeline, which post-processes an item, allows us to store the data in any format (i.e. A database). See Feed Exports in the Scrapy documentation for more information.

Legalese and Scraping Etiquette

If you notice in the crawler execution command above we’ve assigned a value to the DOWNLOAD_DELAY setting. This is important scraping etiquette, as many sites mistake web crawlers for Denial-Of-Service (DOS) attacks since a web crawler can essentially bombard a server with requests in a manner very similar to a DOS attack. In fact, many web sites try to circumvent DOS attacks (and web crawlers in some cases) by prohibiting users with abnormal web browsing activity. You should always consider this, when building your crawler, and use reasonable delays between your requests.

If you think I’m joking, just try running that command above with a delay of 0 (Scrapy defaults to 3) and see what happens… Hehe, don’t worry, you’re access will be restored in a few hours.

It is important to remember that scraping data from websites is usually bypassing the content author’s intended use of the information. Most websites expect users to view their information at a reasonable pace, and even at pro-football-reference.com they’ve taken considerable steps to allow the user to make personal use of the data offline. And, just because you can doesn’t mean you should. It’s always important to read the website’s terms of use, so you understand the conditions placed under the data your extracting. And if you’re doing serious crawling you should also take a look at their robots.txt file so that you understand the rules for web crawling services. A robots.txt file is used by most large websites and is usually utilized by search engines and other massive crawling services.

Wrap-up

The point of this blog was to provide you with a more comprehensive walk through of creating a basic web crawler in Scrapy. So many time the basic tutorials on the web lack the complexity to allow you to do any real work so I’ve tried to provide this example as a resource for those looking to see a beginner-intermediate level overview of building a scraper that can extract a large data set spread across multiple pages. In Part 2 we’ll build off of this example and cover more advanced features of the Scrapy framework such as anonymous scraping, custom export feeds, sharing data across requests, and multiple item scraping. My source for this example is provided below along with the 2014 play-by-play game data in CSV, JSON, and Sqlite.